Benzodiazepine overdoses send thousands of people to emergency rooms each year, and many wonder whether Librium, a long-acting medication often prescribed for anxiety and alcohol withdrawal, carries the same risks.

Yes, you can overdose on Librium (chlordiazepoxide), and while isolated overdoses often respond to supportive care, benzodiazepine-involved fatalities overwhelmingly involve co-ingestion with opioids or alcohol.

This article explains Librium overdose symptoms, the risk factors that turn sedation into a life-threatening emergency, and the evidence-based strategies that can prevent avoidable harm.

What is Librium and How Does It Work?

Chlordiazepoxide is the first clinically deployed benzodiazepine, introduced in the 1960s for severe anxiety and alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Although the Librium brand has been discontinued in the U.S., generic chlordiazepoxide remains widely available. It works by enhancing GABA-A receptor activity in the brain, producing anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative-hypnotic, and muscle-relaxant effects.

The medication has a long elimination half-life of roughly 5 to 30 hours, and its active metabolite desmethyldiazepam can persist with a half-life around 36 to 200 hours. This extended kinetic profile offers sustained relief in alcohol withdrawal but also means that overdose effects can be prolonged and delayed, particularly in older adults and people with liver disease.

Chlordiazepoxide is a Schedule IV controlled substance, reflecting recognized abuse and dependence risks alongside legitimate therapeutic uses. The FDA has issued boxed warnings emphasizing that concomitant use with opioids or alcohol can precipitate life-threatening respiratory depression and coma.

Librium Overdose Symptoms

Overdose on chlordiazepoxide produces dose-dependent central nervous system depression. Common manifestations include drowsiness, confusion, ataxia, slurred speech, stupor or coma, and memory loss. Delirium and paradoxical agitation may occur, though seizures are uncommon in pure benzodiazepine overdose.

Respiratory symptoms include shallow or slowed breathing, which becomes markedly worse when Librium is combined with opioids or alcohol. Cyanosis may appear in severe cases. Cardiovascular effects are usually mild in isolated benzodiazepine overdose but can include hypotension and, less commonly, tachycardia or irregular rhythm when co-ingestants are involved.

Other signs include blurred or double vision, nystagmus, nausea, abdominal pain, and cool or clammy skin. In severe polysubstance overdose, especially with fentanyl, profound respiratory depression, hypoxemia, and aspiration pneumonitis can predominate, even if the benzodiazepine dose alone would not be lethal.

Warning Signs Requiring Emergency Care

- Unresponsiveness or repeated failure to arouse

- Slow, shallow breathing, apnea, or cyanosis

- Inability to protect the airway, such as gurgling or vomiting without a gag reflex

- Severe confusion, delirium, or agitation combined with sedation

- Known or suspected co-ingestion with opioids, alcohol, or unknown substances

Prompt activation of emergency services is warranted for any of these signs. Naloxone should be administered when opioid involvement is suspected or unknown; it will not reverse benzodiazepine effects but can be life-saving for the opioid component of combined toxicity.

Risk Factors That Increase Librium Overdose Danger

Polysubstance Exposure

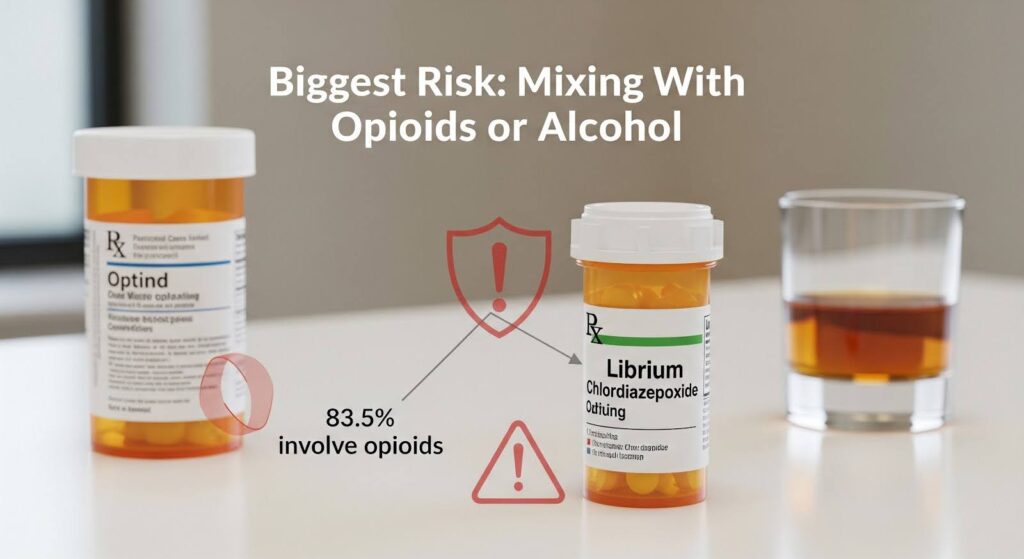

The central lethal-risk driver is co-involvement with opioids or alcohol. In national mortality data from 2000 to 2019, 83.5% of benzodiazepine-involved deaths co-involved opioids. Alcohol was also frequently present in emergency department visits and deaths. Combining benzodiazepines with opioids or alcohol intensifies sedation and respiratory depression through synergistic effects on central respiratory drive.

This risk motivated the 2016 FDA boxed warnings advising clinicians to avoid or minimize co-prescribing, use lowest effective doses, and counsel patients on breathing risks and avoiding alcohol.

Age and Comorbidity

Older adults face disproportionate risk. Poison center data from 2015 to 2022 in adults aged 50 and older show most intentional benzodiazepine poisonings were suicide attempts, with increased odds of major effects or death in advanced age and with co-use of prescription opioids and psychotropics.

COPD and other pulmonary comorbidities amplify respiratory-depression risk from combined opioid–benzodiazepine exposure. Hepatic disease slows oxidative metabolism, causing active metabolite accumulation that can prolong sedation and increase aspiration risk during prolonged obtundation.

Intentionality and Mental Health

In benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths without opioids, 36.2% were suicides, compared with 8.5% when opioids were present. Poison center data indicate higher odds of a reported case being a suicide attempt when co-used with antidepressants, anxiolytics, or alcohol. Screening for suicidal ideation and addressing underlying mental health conditions are central to risk mitigation.

Prescribing Patterns

The 2016 FDA boxed warning precipitated modest declines in opioid–benzodiazepine coprescribing, especially among women and those aged 50 to 65, but did not eradicate the practice. Emergency department data showed a post-warning decline in co-prescribing at discharge, though overall co-prescribing remained detectable nationwide. Incident benzodiazepine prescribing decreased roughly 9% between April 2018 and March 2022, but nurse practitioners’ share of new benzodiazepine prescriptions rose, trends relevant to access, monitoring, and education.

The Scope of Benzodiazepine-Involved Overdose Deaths

From 2000 to 2019, 118,208 benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths occurred in the United States. Rates increased from 0.46 per 100,000 in 2000 to 3.55 in 2017, then decreased to 2.96 in 2019. The majority of deaths involved White males, but rising rates among Black individuals after 2017 underscore persistent and shifting demographic disparities.

In 2019, the U.S. recorded 70,630 drug overdose deaths overall, with an age-adjusted rate of 21.6 per 100,000. Benzodiazepine-involved deaths sit within this broader, evolving polysubstance overdose crisis. Provisional and subsequent data from 2021 to 2024 show continuing high overdose mortality, with benzodiazepines frequently co-involved, including illicit benzodiazepine analogs that compound risk when mixed into a fentanyl-dominated drug supply.

Librium Abuse and Addiction Potential

In September 2020, the FDA updated all benzodiazepine boxed warnings to emphasize risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal. The update was informed by data showing extensive long-duration dispensing, high emergency department visit burdens from nonmedical use, and frequent opioid co-involvement in benzodiazepine deaths.

Physical dependence can develop within weeks of regular use. Abrupt cessation can precipitate severe withdrawal, including seizures and, in rare cases, catatonia. Withdrawal may be protracted in some patients, lasting months and necessitating gradual, individualized tapers with vigilant monitoring, especially in older adults and those with comorbidity.

Patients with generalized anxiety, insomnia, and substance use disorders may be at higher risk of misuse due to the rapid relief benzodiazepines provide. Optimizing non-benzodiazepine treatments such as SSRIs, SNRIs, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, and psychotherapy, along with employing time-limited benzodiazepine use with clear discontinuation plans, can reduce long-term dependence and overdose risk.

Emergency Management of Chlordiazepoxide Overdose

Initial Priorities

Emergency care focuses on airway, breathing, and circulation. Airway management includes positioning, suctioning, and consideration of endotracheal intubation if the patient cannot protect the airway or ventilate adequately. Supplemental oxygen and ventilation support are provided as indicated. Naloxone should be administered when opioid involvement is suspected or unknown; it will not reverse benzodiazepine effects but can be life-saving for the opioid component.

Intravenous access, hemodynamic monitoring, and fluids are provided if hypotension develops. Activated charcoal is generally not indicated for isolated benzodiazepine overdose unless a massive ingestion occurred within one hour and the airway is protected.

Observation and Disposition

Pure benzodiazepine exposure that remains asymptomatic after four to six hours of emergency department observation may allow discharge with safety counseling and follow-up. Persistent mild symptoms warrant ward observation. Severe toxicity requiring oxygen or ventilatory support necessitates intensive care unit admission.

Flumazenil: Use with Extreme Caution

Flumazenil is a benzodiazepine antagonist that is not for routine use in benzodiazepine overdose. It is contraindicated in unknown or mixed overdoses, benzodiazepine tolerance or dependence, seizure disorders, or when the ECG suggests co-ingested tricyclics such as QRS prolongation.

Risks include seizures and dysrhythmias, particularly in mixed ingestions or in tolerant patients. If used in carefully selected cases, such as iatrogenic oversedation in benzodiazepine-naïve procedural sedation or accidental pediatric ingestion with isolated benzodiazepine exposure, adult dosing is 0.2 mg IV over one to two minutes, then 0.3 to 0.5 mg every one to two minutes to a maximum of 1 mg. Re-sedation is common due to flumazenil’s short half-life of roughly 50 minutes, sometimes requiring repeat dosing or infusion with continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring.

Flumazenil does not reverse barbiturate, ethanol, or opioid effects; it is not an antidote for polysubstance central nervous system depression. Case literature documents prolonged flumazenil infusions for long-acting benzodiazepine toxicity, with risk of resedation if stopped too early. This strategy is reserved for carefully selected patients after toxicology consultation, with full recognition of seizure risk and the need for intensive care unit-level monitoring.

Prevention and Harm Reduction Strategies

Prescribing Safeguards

Avoid or minimize benzodiazepine–opioid coprescribing. If unavoidable, use minimal effective doses and shortest durations, coordinate care, and monitor closely. Prefer non-benzodiazepine therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, SSRIs, SNRIs, or buspirone for chronic conditions. Use benzodiazepines time-limited and with a taper plan.

In older adults and those with pulmonary disease, be especially conservative. Symptom-triggered regimens with close monitoring and alternative agents such as lorazepam may be preferable in hepatic impairment.

Patient Education and Safety Planning

Explicitly warn about alcohol and opioid co-use risks. Advise against driving or hazardous tasks when sedated. Provide naloxone when opioids are co-prescribed and educate households on emergency response. Discuss dependency risks and the importance of gradual tapering, and schedule check-ins.

Suicide Risk Management

Screen for suicidal ideation among all benzodiazepine users, especially older adults or those co-using antidepressants or alcohol. Address underlying mental health needs, consider lethal-means safety counseling, and arrange close follow-up.

Key Takeaways

| Risk Factor | Evidence | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥60 | Reduced clearance, enhanced CNS sensitivity | Prefer alternatives; if using Librium, lower doses, strict caps, close monitoring |

| Hepatic impairment | Slowed oxidative metabolism leads to accumulation | Avoid chlordiazepoxide; use lorazepam or oxazepam |

| Co-use: alcohol | Additive/synergistic respiratory depression; 14.7–22% alcohol co-involvement in opioid overdose deaths | Screen and counsel; avoid co-use; triage co-exposures aggressively |

| Co-use: opioids | Markedly increased overdose risk; boxed warning since 2016 | Risk stratify; co-prescribe naloxone; careful titration; avoid concurrent initiation |

| Severe symptoms | GCS ≤8, pneumonia, respiratory failure predict ICU admission | Protect airway; early antibiotics if indicated; ICU-level monitoring |

Conclusion

You can overdose on Librium, and while isolated overdoses often respond to supportive care, benzodiazepine-involved fatalities in the United States overwhelmingly involve co-ingestion with opioids or alcohol. Severe outcomes concentrate in older adults, those with respiratory or hepatic comorbidities, and in intentional misuse such as suicide attempts.

The last decade’s regulatory signals modestly bent prescribing trends, but high-risk combinations remain common enough to sustain substantial preventable morbidity and mortality. Clinicians should prioritize avoidance of opioid–benzodiazepine co-prescribing, screen and treat co-occurring mental health and substance use conditions, and counsel explicitly on the dangers of alcohol and sedatives.

In overdose care, support the airway and ventilation, presume polysubstance exposure until excluded, use naloxone when opioids may be involved, and reserve flumazenil for narrow indications. Future gains will come from targeted deprescribing and monitoring in high-risk demographics, improved detection of illicit benzodiazepines in the fentanyl era, and integrated, equitable care models that address the structural and behavioral determinants of polysubstance overdose.

If you or someone you love is struggling with benzodiazepine misuse or polysubstance use, compassionate, evidence-based help is available. Reach out to explore Summit’s individualized treatment options that can support lasting recovery.